Augmented Learning through Fashion Design

January 11, 2013

PROJECTS: Leveling Up

PRINCIPLES: Academically oriented, Interest-powered, Peer-supported, Production centered

TAGS:

There was a lot to take in on my first day at Fashion Camp. Although the formal lessons weren’t scheduled for another few minutes, I had apparently arrived late for the first lesson: the teacher was talking with five youth about the latest trends. One young woman, about 13 years of age, said that she was into “ombre.” The teacher expressed that ombre is “very in right now,” and that they happened to have ombre polka dot fabric at the camp. She told the girls that they might consider incorporating ombre into their drawing lessons for today after they had learned how to draw croquis (or mannequins, as I later discovered). I leaned over to the teacher and asked her what ombre print is. I noticed the girls started to giggle. She left the table, grabbed a large bolt of fabric on the other end of the room, and brought it over to show me. “Ombre print fades,” she said. “See how the polka dots are saturated on one end of the fabric but then fade to a lighter shade of pink on the other end?”

In the lessons that followed, I began developing my fashion vocabulary and learned how it describes not only academic-relevant techniques (requiring skills in math, design, and an understanding of cultural history) but also a broader relationship to the fashion industry and production. The fashion camps provide important settings for researchers interested in new media and learning across diverse educational contexts. During my ethnographic participation in these camps for the past four months, I have learned that the camp leaders do not see their work as strictly new media technology-driven. In fact, they believe that some skills needed in fashion design (including sketching, creating and using cutting templates, and competency with sewing machines) are often best learned through a mixture of mentorship during in-class activities as well as augmented learning through new media. In this way, the camps provide interest-driven, girl-centered learning contexts that are supported by new media in ways specific to the learning objectives at hand. By augmenting learning with new media, teachers are able to expand the range of their lessons and provide learning opportunities tuned to the skill level of the student. Like the hundreds of students from Southern California who attend the camps to pursue their interest in fashion, I, too, was starting from the ground up by learning fashion sketching in a room with people at different levels of expertise.

A couple of hours into our drawing lesson, the teacher explained that sketching is not just about drawing something pretty but it is also a blueprint for you and for others, as well:

“Say, for example, you need to send the design to a company that produces garments. One way to do this is by creating dotted lines called stitching lines. They tell the company where to sew the fabric.”

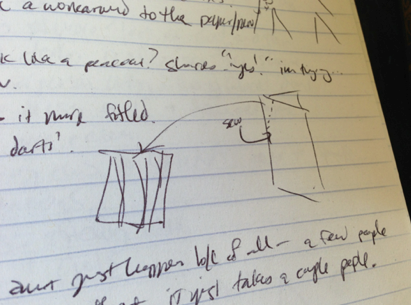

Figure 1: My attempt at sketching a t-shirt that includes stitching lines (- – -), or marks that indicate where to sew the fabric.

Students learn how to sketch in ways that are inherently tied to collective understandings of design and production. In the above example, stitching lines are composed of small darts, or dashes, that indicate where to sew. We also learned how to draw symbols for types of fabric, such as wool or leopard prints, using combinations of markings and labeling. Additionally, most sketches must be constructed with mind to their three-dimensional final product. For example, we learned how to draw ruffles on skirts to indicate how they would look and fit when produced and inverted.

Figure 2: An example of how sketching must be done with mind to three-dimensional final products. Stitching lines on the corner of a folded fabric (drawing on right) results in fitted pleats when sewed and inverted (drawing on left).

As shown in Figure 2, stitching lines on a folded piece of fabric will result in pleats once the fabric has been sewn and flipped inside-out. While students are sketching on a two-dimensional pad of paper, their designs are inherently social: they are learning to convey to others how garments are constructed in three dimensions and how others are involved in different steps of the production process.

Teachers at the camp also use new media as a way to augment their lessons, providing new challenges and opportunities to learn for students at different skill levels. One way the camp engaged in augmented learning practice was through their lesson on designing themed collections. As a designer for a fashion company, the teacher expressed that her drawing process is a lot like her process in the industry:

“I need to run my designs by my boss, and to convince your boss that your drawing is worth producing it helps to create a story around it so it’s easier to understand your outfits. This story can take the form of a theme.”

The teacher instructed students on how to build garments around themes at their own pace while using fashion magazines and websites like Polyvore. Polyvore is a new media-centered web community that allows users (both fashion companies and everyday people) to share images of fashion designs they enjoy. One way the teacher suggested students could use Polyvore was to find a picture of a piece of jewelry they like and then draw a whole collection around that specific garment or piece of jewelry. Another way, she suggested, was to find outfits on Polyvore and then redraw them, over and over, using different colors and patterns. In this way, new media is used to augment the learning process. Students at different skill levels are able to learn a complex set of skills and fashion vocabularies using resources, both online and offline, to enhance their learning.

In my subsequent posts on this case, I plan to discuss how fashion camps operate as an interest-driven, peer-supported, and production-centered learning community focused on academically oriented skills such as math, design, and history. Additionally, through interviews with not only teachers but also the youth and their parents, I hope to examine how connected learning principles may occur across different levels of the learning ecology: these camps operate as one of many locations where youth learn about fashion. However, the fashion camps are a key nexus in the learning process to build specific skills, design garments, work with peers, and provide mentorship.

And they usually leave with a cool new skirt, too.