Digital deception: legal questions surround new “YouTube Kids” app

January 5, 2016

PROJECTS: Preparing for a Digital Future

TAGS: online advertisement, Social Media, YouTube

As the YouTube Kids app was launched in November 2015 in the UK and Ireland, nine months after it hit the US market, Dale Kunkel discusses how Google is stirring the debate on what is and what isn’t acceptable when it comes to advertising to children. In April 2015, Dale partnered with a coalition of 10 public interest and child advocacy groups to file a formal complaint with theFederal Trade Commission against YouTube Kids. Dale is Professor of Communication at the University of Arizona and he studies the effects of violence, sexual content, and advertising on young people.

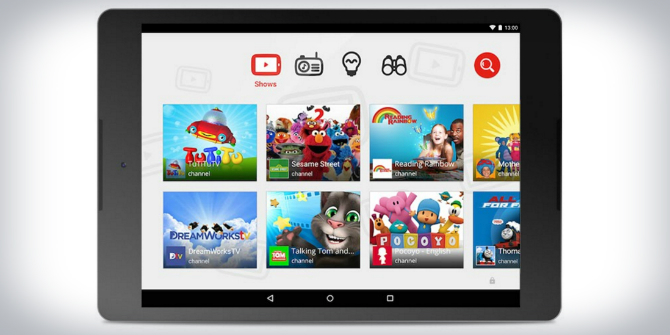

Its creators designed YouTube Kids as ‘the first Google product built from the ground up with little ones in mind’, delivering short videos for two- to five-year-olds on tablets or mobile devices. Google promised only ‘child-safe’, ‘family-friendly’ content would be available – videos that ‘make parents nervous’ would be screened out. YouTube Kids provides about 100 ‘channels’ to choose from, including marquee contributors such as Sesame Street, Reading Rainbow and Disney.

When I first tried it, I was astonished at what I found – it was the most hyper-commercialised media environment for children I had ever seen, an alarming trend that Sonia Livingstone and Ellen Helsper are investigating in a new research project. Indeed, many of the advertising tactics are considered illegal on US television because they intermingle product promotion with entertainment content. This seemed wrong to me, so I resolved to do something about it.

Credit: YouTube

Pervasive advertising

Looking past the handful of bedrock children’s TV titles, I was amazed by the number of offerings centred on commercial products – entire channels devoted to LEGO, Barbie, Play-Doh and even McDonald’s. Many toy channels offer videos that are infomercial-style descriptions of various toys; others depict featured products in classic ‘programme-length commercial’ animated story environments, such as ‘Lego Friends’ or ‘The Barbie Diaries’. Standard TV advertisements for each channel’s products are also available for users to select as their chosen content.

Evantube HD, one of the most popular channels on the regular YouTube platform, offers a different type of commercialisation. Evan, a precocious eight-year-old, stars in videos that present him engaging with featured products in an entertaining context. In one episode, he goes on a trip to Disneyworld; in another, he tastes various flavours of Oreo cookies while blindfolded, trying to guess which flavour he is eating. This is product placement at its finest.

Another popular user-generated video innovation is the ‘unboxing video’, found on many YouTube Kids channels. These feature anonymous children opening a new toy package and experiencing the joy of discovery – they ‘ooh’ and ‘aah’ gratuitously.

And if the degree of commercialisation in the so-called ‘content’ isn’t sufficient, what Google calls ‘pre-roll’ ads appear randomly in between every second or third video segment watched.

YouTube Kids presents advertising to children in unprecedented volume, while ignoring longstanding policies that restrict certain commercial practices during children’s TV programmes, such as host-selling and programme-length commercials. If advertising practices like these are considered unacceptable on a TV screen for children’s viewing, why should they be allowed on the small screen of a mobile phone or iPad?

Blurring the boundaries between entertainment and advertising content

As children’s use of electronic media has migrated from TV to the internet, online media providers have devised a host of innovative commercial practices that blur traditional boundaries between entertainment and advertising. And as these practices have grown, the absence of any attention from regulators seems to suggest that digital advertising to children can be whatever the market allows.

In the US, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulates TV, but holds no authority over internet content – responsibility for regulating advertising to children on the internet and in other domains falls to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

In April 2015, I partnered with a coalition of 10 public interest and child advocacy groups to file a formal complaint with the FTC against YouTube Kids. Our complaint noted that the FCC has long required a clear separation between children’s TV programmes and advertising content. This ‘separation principle’ is the conceptual foundation for the policies that restrict host-selling and programme-length commercials on television. When it established those policies in 1974, the FCC ruled it was ‘unfair and deceptive’ to blur the boundaries between commercial and entertainment content targeted at children. Our legal complaint alleges that advertising that is intermingled with children’s entertainment online is unfair and deceptive, just the same as it would be on children’s TV.

While Google is hardly the first online company to intermingle children’s entertainment and advertising, YouTube Kids represents the biggest and most aggressive threat to traditional norms of acceptability for advertising to children. A ruling that upholds our complaint could establish an important precedent that child-targeted advertising must be clearly distinct from entertainment content in all media, not just TV.

Objectionable content

After filing our initial complaint focused on advertising, my colleagues and I learned that YouTube Kids affords access to a huge volume of inappropriate content for children. A voice-activated search function helps pre-literate children explore any topic they choose, but to our surprise, we found that the search goes well beyond the curated children’s channels, providing access to a broad range of videos posted on YouTube, many intended for adults.

While Google claims to filter out any content unfit for children, using the search function, we encountered dozens of videos with sensitive material, including indecent language, jokes about drug use, discussions about parents who kill their children, and commentary on teen suicide. Thus, we supplemented our initial complaint to the FTC, arguing that Google misleads parents by claiming to provide a product they can trust without the need for careful monitoring. We submitted a video documenting the problems to the FTC in May 2015.

Changes to the policy landscape?

The FTC is currently investigating our claims. If they uphold our complaint, it could establish a landmark precedent that child-targeted advertising must be clearly separated from entertainment content in digital media, the same as on TV. If they don’t, advertisers will be allowed to employ significantly more powerful tactics online than on TV, an outcome that is contrary to the longstanding policy of protecting children from unbridled commercialism on electronic media.

Should the latter outcome occur, I suspect that companies that rely on ‘pester power’ to sell products such as toys and sweets to children may soon breach other traditional boundaries. ‘Boys and girls, ask your mom and dad to buy you…’ may soon return to advertisers’ vocabulary after being banished back in the 1970s. This would pose new challenges for parents, and no doubt increase parent–child conflict from more frequent purchase request denials.

Profits versus child protection are the stakes in this battle, just as they have been so often in past media policy controversies. Will the advent of digital media be an excuse to alter the policy landscape in favour of advertisers, or will regulators apply the same principles adopted in the past to contemporary media? The outcome in this case should go a long way toward answering this question.