Digital Skills Matter in the Quest for the ‘Holy Grail’

April 7, 2017

PROJECTS: Preparing for a Digital Future

TAGS:

As part of the European Commission Study on the impact of marketing through social media, online games and mobile applications on children’s behaviour, Sonia Livingstone and her colleagues published an analysis of a survey of 6,400 European parents to see whether they are finding the ‘holy grail’ of managing their children’s internet use. Today is Safer Internet Day, and Sonia takes a closer look at how European parents try to optimise their children’s online opportunities while also minimising their online risks. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project.

Image credit: L. Farzati, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

As parents equip their homes with digital media, most advice urges them to restrict their children’s internet use to reduce risk. While the risks are real, and need to be addressed, this advice is out of sync with parents’ experiences of the realities of daily family life in the digital age, and pays little heed to parents’ desires also to maximise their online opportunities. Much of that advice also assumes parents’ only options are to restrict digital media or give up, as if they lack the skills needed for more subtle strategies.

Restrictive or enabling mediation

We surveyed 800 interviews with parents of 6- to 14-year-olds in France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Poland, Italy, Sweden and the UK. After asking lots of questions about all the different activities they might do to manage their children’s internet use, we identified two underlying factors:

- Restrictive mediation: a long list of online activities that parents might restrict or ban or insist on supervising.

- Enabling mediation: included active strategies such as talking to a child about what they do online or encouraging their activities as well as giving safety advice. It also included activities that might seem restrictive (use of technical controls and parental monitoring) but are better interpreted as building a safe framework precisely so that positive uses of the internet could be encouraged.

The more parents used enabling mediation, the more their children initiated discussion about their internet use with their parents or asked for advice or help. The more parents used restrictive mediation, the less their children were likely to ask for parental input.

Parents’ choice of strategy depended on how risky they thought the internet was for their child. As parental risk perception rises, parents do more enabling but less restrictive mediation, perhaps following advice that it is better to get involved in their child’s internet use if they are worried. But as parental risk perception rises yet higher, parents intensify both enabling and also restrictive mediation, perhaps believing that enabling alone is insufficient.

Younger children receive more parental mediation and girls receive more restrictive mediation in particular.

A complex choice

Which parental mediation strategy works best for maximising opportunities and minimising risks? Unfortunately, perhaps, our analysis did not reveal the hoped-for strategy that could simultaneously maximise opportunities and minimise risks, the ‘holy grail’. Rather, the findings pinpointed the complex choice that parents face:

- More enabling mediation was positively associated with children’s online opportunities, but also with more risks.

- More restrictive mediation was associated with fewer risks, but also with fewer opportunities.

This makes it problematic if policy-makers concerned with risk urge parents to restrict children’s internet use without recognising the costs to their online opportunities. But also problematic is the tendency of educators to urge parents to enable children’s internet use without recognising that this may bring more risk.

A promising direction

To escape the costs of either approach, the present findings regarding digital skills suggest a promising direction. Interestingly, parents are more restrictive if they judge themselves less skilled. Conversely, the better the parental skills, the more parents prefer enabling mediation. This is possibly a more demanding strategy for parents, or more skilled parents may be more aware of the online opportunities available, and so choose not to restrict their child. It’s also possible that more skilled parents may be confident that they and their children can deal with risk when it occurs, thereby avoiding or minimising actual harm.

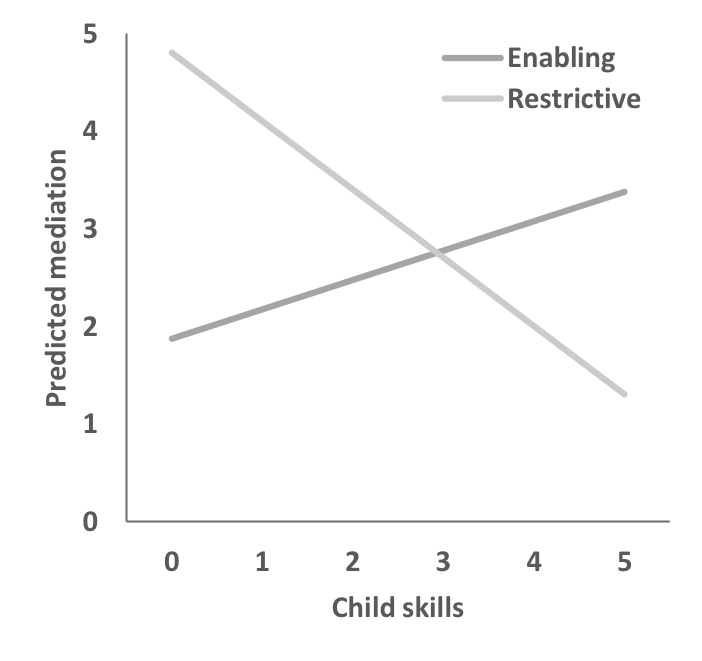

We also found that parents favour restrictive mediation when they judge their child to be lower on digital skills, but they turn to enabling mediation the more they judge their child to be digitally skilled. Controlling for a range of relevant variables, this finding is shown below:1

Encouragement and support

Parents respond to their child’s internet competence and experience. They prefer a risk-averse restrictive strategy for less skilled children, presumably doubting their child’s ability to cope with risk if they encounter it. And they are more encouraging and supportive of their children online if the children are, or as they become, more competent internet users.

It is time for researchers, policy-makers and parents to rethink the dominant emphasis on harm in parenting advice. Many parents are skilled in using the internet, and use their skills to support their child’s emerging digital skills and interests in ways that are responsive to their child’s needs, building safety considerations into an overall enabling strategy. Those who are less confident of their or their child’s digital skills take a more restrictive approach, keeping their child safe, but at the cost of online opportunities.

Policies to improve digital skills for both parents and children would therefore be beneficial in maximising opportunities, provided that this is combined with efforts to enhance children and parents’ coping strategies and resilience in the face of risk, so that it does not lead to actual harm.

Notes

1 The child’s digital skills were measured on a scale from 5 = very true of my child to 1 = not at all true of my child. Enabling mediation was measured on a scale from 5 = always to 1 = never, asked of a series of activities. Restrictive mediation was measured on a scale from 5 = can do [list of online activities] anytime to 1 = can never do this. All scales have been standardised.

This article originally appeared on lse.ac.uk. It has been re-posted with permission.