Exploring interest-powered learning in informal game design clubs

May 10, 2013

PROJECTS: Leveling Up

PRINCIPLES: Academically oriented, Peer-supported

TAGS: Kodu, mentorship

Guest blogger biography: Gabriella Anton is currently a research specialist and the project manager of Studio K at the Games+Learning+Society Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her current work focuses on examining the educational and computational thinking benefits of learning game design. More broadly, she’s involved in the study of interest-powered learning, especially in online communities.

Finding my Motivation

I grew up as a Montessori student with a Montessori teacher for a mother. In seventh grade, our family moved and I first experienced traditional schooling – enrolling in the local public school. That first year was eye-opening for me primarily because I began to see that, unlike my Montessori teachers, many of my traditional teachers did not expect me to challenge myself, maintain genuine interest in content, or be a co-designer in my education. It was around this time that I first decided that I wanted to work in the education field to help create opportunities for other students to find the same genuine interest in learning that I had found through my experiences with Montessori. Over the years, I’ve only become more appreciative of my first Montessori teachers and the handful of public school teachers who were able to instill the desire to learn in me.

Since that turning point in my life, I have consistently been involved in projects related to my passion for education: first running after-school programs at a local school, then becoming a classroom assistant at a Montessori school, and now studying interest-powered learning in after-school clubs and online communities. To me, nothing is as meaningful as the deep engagement that occurs with pure interest-powered learning. One of my goals in life is to help propagate this experience.

Studio K

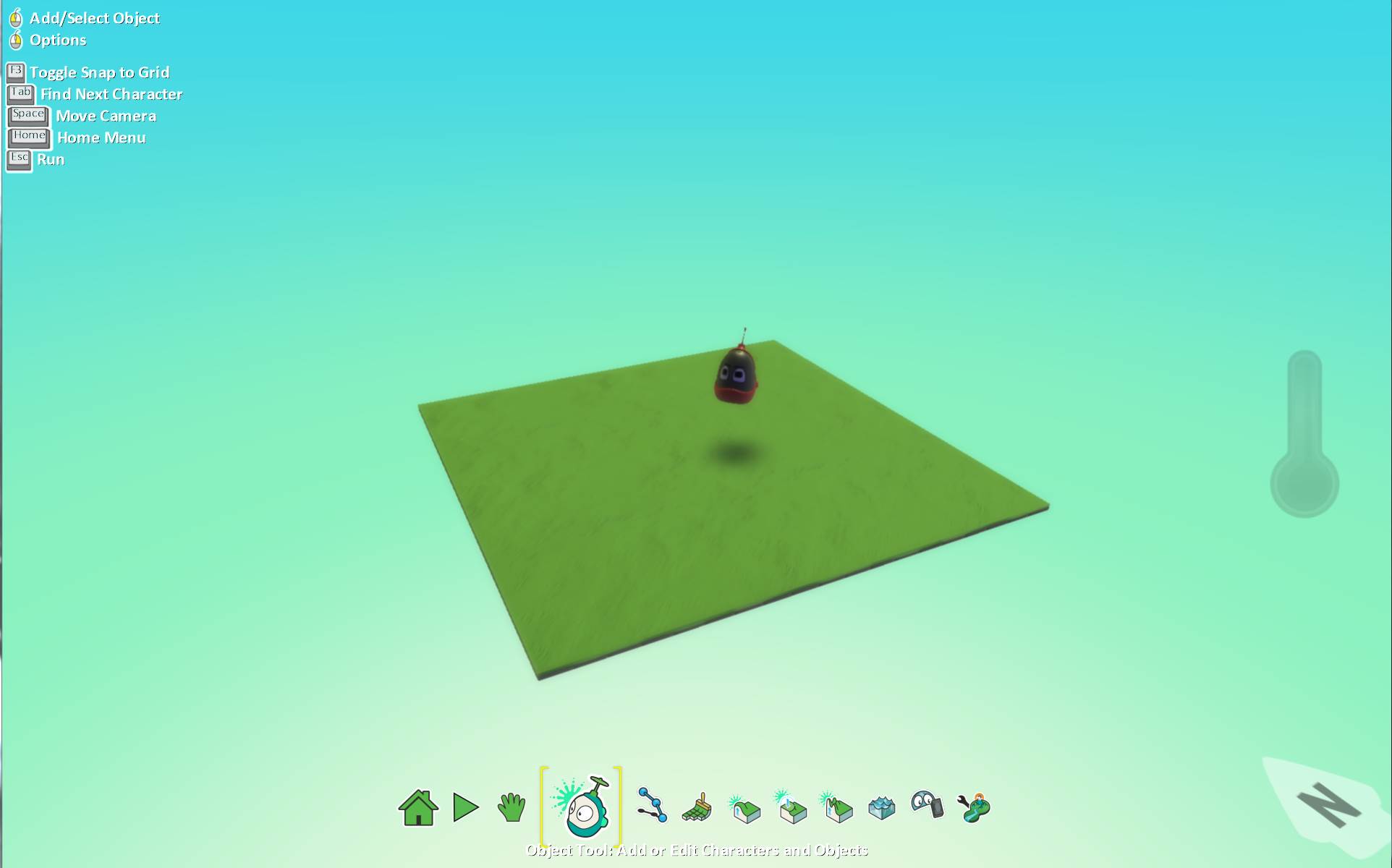

Aligned with my passion for education, my current work focuses on creating an environment that will encourage interest-driven, peer-supported learning. For the past year and a half, I have participated as a research specialist and project manager for a group of developers and researchers at the Games+Learning+Society Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison designing and implementing an online curriculum to teach game design. Our hope is that through initial interest in games, youth will gain the desire to program while acquiring computational thinking skills. The project, Studio K, encourages creative design, critical thinking, and problem solving through a series of challenges that have youth creating and revising games with the Microsoft game design software Kodu (see screenshot below). While the curriculum is academically oriented, the challenges are designed to give students creative freedom in how they progress through the curriculum and what they focus on during design, allowing students to become pilots for their education – encouraging interest-powered exploration.

Interface for Microsoft game design software Kodu

Power of Play

We feel a constant energy from the youth during each of our game design club sessions. From the time they excitedly enter, chatting about their day and their game design goals for the session, to the time spent designing in full swing while a quiet lull descends on the club, it’s easy to recognize that these youth are focused and determined to make the games in their imaginations come to life. Day-by-day, one can see the progress these youth make in acquiring game design skills – resolutely working through bugs and snags in their designs. Since the program facilitates interest-powered trajectories through the curriculum, learning and engagement in these clubs can look very different from youth to youth.

Youth participating in a Studio K afterschool programYouth participating in a Studio K afterschool program

Youth participation in the clubs follow trajectories that I classify with three main categories: 1. the “Player”, characterized by heavy exploration of gallery games before slowly creating games, 2. the “Fixer”, characterized by heavy exploration and modification of gallery games leading into applying techniques while creating games, and 3. the “Creator”, characterized by immediate creation of games, often learning by trial-and-error. The mixture of these participation styles in the clubs helps to facilitate peer-supported learning. The diverse activities that occur during a typical game design club session encourage peer mentorship and exploration of new practices.

At one site in particular, a unique relationship formed between two youth, one a “Player”, Devon, and the other a “Creator”, James (both pseudonyms). From the start of the program, it was obvious that these two fifth grade boys would be really motivated and interesting students to follow. Both were outgoing, immediately introducing themselves to me and describing in great detail their excitement and the games they wanted to make during the program. Beyond their initial friendly behavior, their participation in the club differed greatly.

Devon had a younger brother in the program that he helped to keep on track throughout the ninety-minute club sessions. He ran a constant commentary on his own work, remarking on the many gallery games that he played at least a half dozen times each. He was also very aware of the other club members’ activities, frequently stopping his personal work to look over others’ shoulders. By the end of our club session, he had made a few games with other youth in the club that they would return to in order to perfect them.

Land design in one of the games, ‘The Wild Land’, which Devon created with another club member.

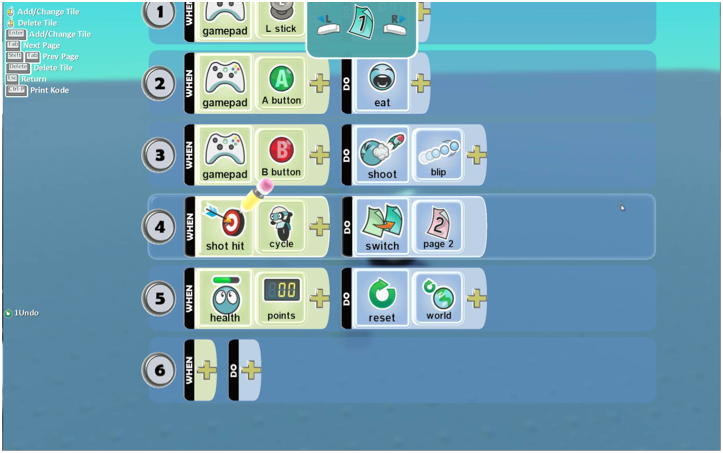

Conversely, James primarily worked alone, getting caught up in his design work. From the first day, he launched wholeheartedly into his own designs, completely bypassing the gallery games. He would enter each club session while chatting with his friends about the day and then would very seriously turn to Kodu. Occasionally someone would get his attention, generally after several repetitions of his name and tapping his shoulder. Besides these infrequent distractions, James would interact with the organization’s club facilitators – either showing off his progress or asking for some guidance while programming. By the end of our club session, he had a dozen games featuring the new programming techniques he was working through.

Programming from James’ first game, ‘Moon Game’, in Kodu.

While originally seeming to be distracted by others’ work, after a few days, Devon’s focus became more honed on James’ work than other youth in the program. He’d often stop to look over James’ shoulder, occasionally asking questions that James would quickly answer. Devon admired James, often commenting on how cool his levels were or asking him to work together with him on a game project. One could see how James’ influence on Devon guided Devon’s participation in the club. After seeing James’ continual work with programming, Devon began to look at each object’s programming in the gallery games, reading aloud the code and commenting, “what does that do?… oh, that makes sense.” As Devon became more confident in his own game-making skills, he started to share his design with James, and their relationship evolved toward more equal collaboration rather than pure mentorship.

The power of Studio K comes from its ability to facilitate interest-powered learning that is bolstered through peer-supported interactions with the content. While the content is academically-oriented, the experience facilitated by the curriculum is non-traditional with a production-centered focus which encourages creative exploration of interests. Youth are asked to complete challenges and share their work with each other, but the path they take through the content is unique to their interests. Unlike a traditional learning environment, each youth was able to find his or her own way to interact with the content. This unique setting provided the means for students to have more meaningful interactions with each other, often fueling the discovery of new practices or techniques. The informal setting for these clubs supports the development of relationships, like the one between Devon and James. Across each club, webs of mentorship form as students discover and show off their expertise. Since the setting is so informal and collaboration is encouraged, students become resources for each other – each having his or her areas of expertise recognized by others in the clubs as they become the go-to person for help on certain areas of the curriculum. Studio K and similar programs or environments which promote the principles of connected learning redefine learning for students, motivating and inspiring youth to learn and apply their skills in creative ways in daily life.