Why study parenting from a media studies perspective?

August 21, 2015

PROJECTS: Preparing for a Digital Future

TAGS: Digital Family, family life, parents

Sonia Livingstone discusses how traditional research disciplines have long caused a division of theories, ideas and conversations that fragmented the field. She argues that the internet brings all of these forms of scholarship together and how it makes media studies a potent approach to investigate parenting for a digital future. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project.

Does it puzzle you that our project on parenting for a digital future comes out of a department of media and communication, rather than, say, a department of sociology or psychology or social policy?

First, our approach is strongly inter- and multidisciplinary. Sonia was originally trained as a social psychologist, Alicia an anthropologist, Julian an educationalist and Svenja a media and communications researcher. Now we all work in a department of media and communications in which a great diversity of approaches and topics thrive.

Second, families are being studied in the social sciences from a dizzying array of perspectives – ours is just one, and our aim is to add our insights to the wider mix, encouraging debate and discussion.

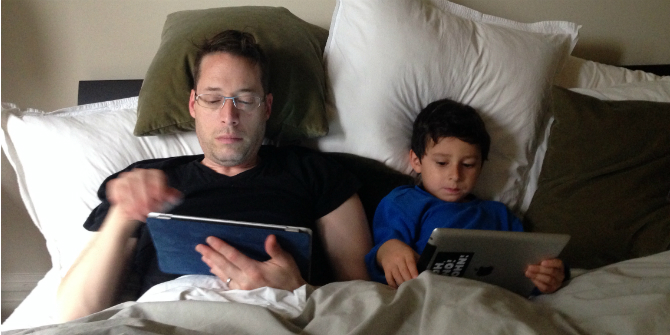

Credit: Davitydave, CC BY-NC 2.0

In a recent post, we asked a crucial question – why label our time and life digital, as it relates to childhood, to family life, to parental visions of the future? The answer is still unfolding, but clearly digital media are reconfiguring daily life in complex and multifaceted ways. It’s not that they make no difference. But nor has life been transformed beyond all recognition since the invention of the internet. Indeed, understanding those complex changes as they reshape family life is a task for researchers, for society, and for parents themselves.

But taking a Western media studies perspective isn’t such a straightforward or unproblematic decision. We have long suffered a division in our theories, ideas and conversations – between those who study ‘the media’, and those who study how individuals communicate with each other. In the American discipline of ‘communication’, both traditions were huge. Consider the structure of the International Communication Association (ICA), for example, with its divisions of mass communication (traditionally the largest), interpersonal communication and, developing out of the latter, organisational communication. In other countries, the field has been divided differently again, drawing on different kinds of theory, disciplinary knowledge and methodological preferences.

In the UK, for example, we focused on ‘media studies’, in the institutions and texts of media and cultural industries. We took our theory of power from the Frankfurt school of critical theory in Germany, our theory of texts from French scholars of semiotics and structuralism and, rather short-sightedly, we left interpersonal communication to social psychologists.

Meanwhile, quite separately, in departments of literature and linguistics, there were scholars of print literacy, while anthropologists interested in the cultural narratives, rituals and traditions that create community were working somewhere else again. And many scholars were inclined to reject as technologically determinist the ‘medium theory’ developed by Canadian scholars following McLuhan’s famous notion of technologies as ‘extensions of man’; again, this was short-sighted, as such work is now enjoying a resurgence with the arrival of wearables and other smart technologies.

So, until about 20 years ago, scholarship consisted of culturally (or nationally) distinct traditions for analysing technologically distinct media technologies and forms, with a heavy emphasis on mass broadcasting and little connection to those studying print, telecommunications or other ‘marginal’ media. No wonder the journals were full of despair about the fragmentation of the field!

It took the advent of the newest and most absorbing complex and global medium of all – the internet – to bring all these forms of scholarship together! Because simultaneously, the internet integrates and connects all media. This means that each addition or change alters – or remediates – the meaning of all other media by altering their position in the wider media environment. Thus the internet not only adds new forms (websites, social networks, chatrooms), but it also simultaneously encompasses and alters the meaning of older forms (e.g. reading books becomes a more specialised choice, or new written formats emerge such as the ‘blog’, or videos get much shorter and are watched on YouTube via a ‘playlist’).

What’s fascinating is that, notwithstanding widespread anxiety about how everyone is staring at their screens rather than at each other, interpersonal communication is the ‘killer app’. This is now radically underpinned by digital (and largely commercial) networks of global reach (consider the unexpected yet staggering success of email and social networking services). And face-to-face communication is also possibly being remediated by the advent of ever more mediated channels and platforms – valued afresh for its privacy, flexibility and authenticity.

But still, it’s as if we have only just observed that, first and foremost, what people do, what people have always done, is talk. They talk all the time – they talk intimately, they talk in groups, they talk to people they hate, they talk to everyone and no one, they talk to themselves. It’s what makes us human. And the same is true for children and young people, despite fears that these ‘digital natives’ are forgetting how to be social, as we find in our recent research on The Class.

So yes, we have spent years studying technology – whether as material culture, print, telecommunications, audio-visual, or new media. But really, all along, what we’ve been studying is communication. And it is on the very idea of communication – in whatever form it takes – that humanity pins its greatest hopes and fears.

So why approach parenting for a digital future from a media studies perspective? Because:

- It helps us position digital media within family life, according it neither too much nor too little attention. People still talk to each other face-to-face, and ‘talk’ still happens in mediated forms, including with and among children.

- It allows us to contribute expertise about digital media uses to the wider multidisciplinary study of families. You can hardly treat modern family life as if all sources of influence, knowledge and communication arose only through direct, co-located interpersonal interaction.

- It draws together the two key traditions we now need to understand the internet – interpersonal communication and mass media – recognising that families’ uses of media still largely resembles ‘ordinary conversation’ (although now mediated by social networking or mobile platforms), and resembles in other respects traditional ways of engaging with television or print (e.g. families finding new ways to gather round the shared screen).

- And it helps us to see something we have emphasised before, namely, that ‘the digital’ captures parents’ imagination, crystallising their hopes and fears for their children, giving a ‘sci-fi’ imaginary to their grasp of the future. ‘The digital’ provides a means, a language by which to articulate deeper-seated and harder-to-envisage uncertainties about the role of parents in their children’s digital futures.