What does it mean for children to have a ‘voice’ in research?

August 18, 2015

PROJECTS: Preparing for a Digital Future

TAGS: children, Research methods

Adults such as researchers, parents, teachers, etc. often speak for children and it is important, despite difficult, to figure out effective ways to hear children’s voices directly. Alicia Blum-Ross is part of a group that has brought together researchers from across the LSE to discuss children’s voice and she reflects on the diversity of perspectives.

Over the past year we’ve brought together researchers from across the LSE to talk about practical approaches to and issues that emerge from research with children, young people and families. This research is sometimes marginalized because it involves people of all ages, involves play-based or participatory research methods or focuses on domestic life. Our group was an effort to compare good practice and explore shared ethical and practical and theoretical research questions.

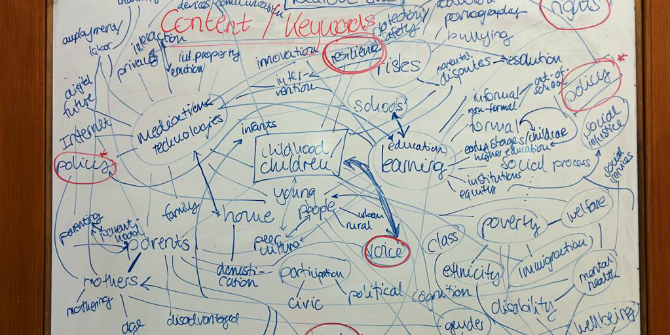

Our first meeting identified some common terms and concepts, our second session explored the term ‘voice’ – a topic on nearly everyone’s minds but a concept about which there is no universal agreement. Here are a few approaches.

Psychology and voice

Sandra Jovchelovitch from the Department of Social Psychology described how child psychologists (including Piaget and Vygotsky) differentiate between stages in children’s ability to talk about their experiences. Although most children acquire language in similar ways – especially before the age of 5 – after that social and cultural factors begin to make a bigger difference. Some children are happy talking abstractly about their emotions and experiences while others remain more comfortable with concrete observations about the world. Equally, not all children are in in the same circumstances. In the global North children may be ‘empowered’ to act as adults but in many contexts (including in the favelas of Brazil where Sandra works), children are acting as adults in uncomfortable and dangerous ways, and researchers need to emphasize play and fantasy in helping to slow down the process of growing up.

Credit: S. Ottovordemgentschenfelde

To illustrate, she talked about her research project where children were asked to make drawings about their participation in public life. These drawings allowed children to participate how they felt comfortable, thus using their ‘voices,’ but also led to problems of interpretation – how could researchers interpret these drawings? Questions included:

- What are the differences between children’s and adult’s ways of knowing and communicating?

- Is there a role for fantasy, art and pretend play in eliciting children’s voices?

- Is it always fair to ask children to have a voice?

- What might be the consequences of asking children to use their voices?

Communicating voices through media

I (Alicia Blum-Ross) spoke from the perspective of media and communications, considering how many media-based interventions – from youth media to citizen journalism – are attempts to engage or amplify the voices of people who are not otherwise ‘heard’ by wider society. In order to understand the impact of these efforts, however, we need to explore what we mean by voice, something Nick Couldry has defined as ‘the capacity to make and be recognized as making narratives about one’s life’. This definition includes both the process of making and expressing voices, along side the ways that voices are heard, and potentially acted upon. In my research with participatory media projects there were instances where young people used their films to challenge the adults who ran or funded the projects, but often these challenges were not listened to. I asked the group:

- How are young people’s voices constrained in visible and invisible ways?

- Is it possible to equally encourage the process of voicing and ensuring that voices get heard?

- How is the idea of ‘voice’ assigned ‘currency’ (sometimes literal when it comes to funding) within the work we all do?

- How do we avoid falling into the trap of ‘fetishising’ youth voice?

Voices in policy research

Having led a large-scale survey (the Millennium Cohort Study which followed 19,000 children across the UK born in 2001, interviewing their parents and then the children directly at ages 3, 5, 7, 11 and 14), Lucinda Platt from the Department of Social Policy reflected on how to build children’s voices into quantitative research. There were several practical and ethical issues that emerged in administering the survey. For example – should the research be open to issues that children wanted to talk about or by-necessity steer towards more sensitive topics like alcohol use that are important for policy research but may be either irrelevant or leading to children? At what age could children give consent? At age 11 the team sent consent forms home ahead of the interview but even at 14 children only wanted to participate if they knew their parents had given the go-ahead.

Ideas around ‘confidentiality’ were hard to communicate. On the one hand the researchers told the children how special they were for participating, on the other they told them their response would be anonymous and mixed in with others. This raised the following questions:

- How do you remain responsive to children’s interests/issues within a large-scale survey?

- How can we acknowledge the relationships of power that exist within families while simultaneously foregrounding children’s agency?

- How can we balance between ‘specialness’ and the particularities of young peoples voices and the needs for generalizability and confidentiality?

- How young can the children be that you listen to and what special provisions are needed to enable very young kids to speak for themselves?

Legal perspectives on voice

From a legal perspective, children are assigned different rights and statuses in legal proceedings from those of adults. Marian Roberts, a lawyer and researcher in the Department of Law discussed how there are competing principles at work in determining how to involve children in family mediation – are children rights-holders and bearers of ‘voice’ or are adult decisions about their welfare (‘best interests’) more important? While the child might have the right to information about what is happening, and the right to express a view, the adults involved also have rights that legal processes need to respect.

Family mediation is nearly always fraught for both children and adults, and is a clear example where children’s ‘voices’ (their spoken understandings) may be influenced by their emotional state and sense of others’ expectations. Even where and when interviews are held might affect what a child has to say. Therefore ‘voices’ may sometimes require extremely sensitive support and in some cases children cannot or should not be asked to ‘speak for themselves.’ Questions raised included:

- Can we assume that either children or parents in deeply emotional/vulnerable settings will be fully ‘competent’ and represent themselves reliably?

- How can we understand ‘voice’ in relationship to power, location, context and that which is spoken versus unspoken?

- What happens when voices are in competition?

These perspectives provided the basis for a thoughtful discussion on what ‘voice’ means within our different disciplines, and how we might think more critically about how to make sure that children and young people’s voices are heard both within and outside the research process. This also has implications for studying families, when we often hear multiple perspectives and ‘truths’ even from within the same family. Perhaps’ children’s voice and listening to it is most needed precisely in situations where parents cannot or do not represent their children well.